Overcoming the Divide: Nonpartisan Politics

Fostering insightful political discourse and debate.

Episodes published bi-weekly on Tuesdays.

To receive updates, participate in polls and promotions follow 'overcoming_the_divide' on Instagram. Rate and subscribe if you enjoy the content!

Overcoming the Divide: Nonpartisan Politics

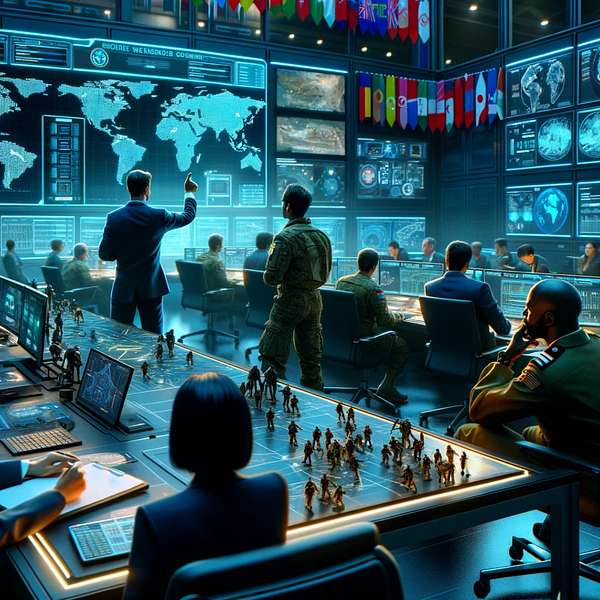

Dissecting the Geopolitics of the War in Gaza with Javed Ali

Uncovering the war in Gaza as we are joined by national security expert, Javed Ali. With more than two decades of experience in national security and intelligence issues, he navigates us through the complex geopolitical landscape, shedding light on the US's steadfast support for Israel, the sizeable aid package in play, and the pressing need for Israel to curtail civilian casualties. We probe deeply into the stances of other key players in the fray, such as Hezbollah and Erdogan, and ponder over the question: is the US unwittingly spiraling into a larger quagmire by failing to address the humanitarian crisis in Gaza?

We tread further down the rabbit hole, exploring the potential aftershocks of a multi-front war between Israel and its adversaries. Javed Ali, with his vast trove of experiences, helps us understand the current turbulence in the West Bank, the strain on Israel's resources due to a two or three-front war, and the probability of escalated US involvement. The conversation harks back to the US' role in Lebanon four decades back, speculating on the possible involvement of US special operations forces in the Gaza hostage recovery and the ensuing implications.

We shift gears towards the possible recoil in Israeli public opinion should the IDF suffer significant casualties. Ali and I draw parallels between the Israeli ground offensive against Hamas and other conflicts while contemplating the Geneva Convention's mandates for minimizing civilian casualties. As we reach the tail end of our discussion, the necessity for an overhaul of Israeli intelligence is considered, along with the geopolitical repercussions of sustained combat. This is an exploration you won't want to miss.

0:00 US Approach to Gaza Conflict

11:44 Israel Conflict and US Involvement

25:02 US Involvement in Israel Conflict

34:56 Israel's Casualties, Public Opinion, Tactics

47:15 Geopolitical Implications and Intelligence Reforms

Music: Coma-Media (intro)

WinkingFoxMusic (outro)

Recorded: 11/3/23

Hello everyone, thank you for tuning in today. Today's episode challenges a number of mainstream positions. It unravels the geopolitical implications of the war in Gaza, flushes out potential responses and approaches the US government could take, and draws parallels from the war in Iraq to the current war in Gaza. This episode features Javed Ali. Ali is an associate professor of practice at the Gerald R Ford School of Public Policy, where he delivers courses on counterterrorism and domestic terrorism, cyber security and national security and policy. Ali brings more than 20 years of professional experience in national security and intelligence issues in Washington DC. He has held positions in the Defense Intelligence Agency and the Department of Homeland Security before joining the Federal Bureau of Investigation. While at the FBI, he also held senior roles on joint duty assignments at the National Intelligence Council and the National Counterterrorism Center and the National Security Council under the Trump Administration. Ali holds a BA in political science from the University of Michigan, a JD from the University of Detroit School of Law and a master's in international relations from American University. He provides TV and radio interviews on a range of national security issues to US and international networks and similar print commentary in such publications as the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Hill and Newsweek.

Speaker 1:If you enjoyed this episode, you take something away from it. All I ask is that you share it with a friend, put also rate and subscribe to the show to make sure you don't miss out on any episodes and future content. Thank you. I prefaced the previous episode with a similar note and I'll do the same for this one as well.

Speaker 1:This is touching on a very sensitive topic for a lot of people. Not everything that is said will probably land well with everyone, which is almost intuitive, but I like to reiterate that time to time, especially on sensitive topics. So if you feel yourself frustrated with the commentary or the questions or the responses, just turn off, not worth during your day over. This episode was also recorded on November 3rd, which was a Friday. That's important because things are constantly in flux and something that you hear during this conversation may not be the most up to date information, since it's about 10 or so days ago. So with that, I hope you enjoy this episode. What is the US government's current policy approach towards Israel, towards the war in Gaza, and is there a difference in that approach and what you believe that approach should be?

Speaker 2:Well, daniel, nice to be with you on the show and the US position at some levels it is. There are some core principles I think the US government has tried to stick with, but if you've listened to what President Biden has been saying, or Secretary of State Blinken or the Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, I do think there has been some shifts over time outside these core principles. Maybe that's based on the reality of what's going on with the second phase of the Israeli campaign into Gaza in response to the attacks on October 7th. But stepping back, I mean President Biden has said that the US support to Israel is iron clad, steadfast, all the words that he has used, that we have their back and that Israel has a right to defend itself because of the horrific attacks on October 7th. So that seems to be a core principle.

Speaker 2:And now there's this debate in Congress about an additional aid package, not only to Israel but also Ukraine, and it looks like I'm not keeping up with everything, every move on that, but it looks like that aid package of about $14 billion, I think, is going to go to Israel in addition to the Ukraine portion of it.

Speaker 2:But also President Biden has said, and Secretary Blinken and others that Israel, now that we're a month into the Israeli response and both the air campaign and now the ground campaign that Israel has to do as much as it can to prevent civilian casualties as it's conducting its military operations. It also has to allow the flow of humanitarian relief from this one very narrow point of border crossing in Egypt, the Ra'fa border crossing that bumps up against the Gaza Strip. And what happens to the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who are in Gaza, who either want to get out or want to know, once the fighting starts, what happens to them and who will be responsible for governing? And these are all really especially that last one, like these are all really tough questions. So I do think the US position is trying to evolve to meet the reality of what's happening on the ground.

Speaker 1:Hmm, when you say when the fight begins it's, I think a lot of people probably contest that and challenge that, as people have seen, with the numerous airstrikes have taken place thus far, as well as the ground invasion that has begun. But we have also seen other actors kind of state their position on this. No, specifically, we're seeing Hezbollah, or Hezbollah who's been engaged, israeli positions, erdogan, state that they will declare Israel as a war criminal to the world, rather than clear what that will mean, or manifest as Iranian back militias are targeting US troops in Iraq and Syria, not to mention the tens of thousands of Muslims and Arabs who are protesting their governments to act on what is currently happening in Gaza as they see it as a war crime. Are we sleepwalking ourselves into a larger conflict by not addressing the humanitarian crisis in Gaza with a more specific, actionable approach?

Speaker 2:Yeah, and I thought I had said already that you know the fighting is a month in, not that it clearly. I mean it is. It has been brutal fighting for a month on, on every side. You know the Israelis are taking losses, the Palestinian civilians are suffering. We don't know how many Hamas fighters have been killed or captured. So I mean this war is in full swing and it's only but it's only a month, and maybe that's the point.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I might miss that, Apologies.

Speaker 2:Yeah, trying to make and no one knows where, you know how long this will go on, for what victory looks like for for either side. I mean, these are again difficult questions. But to your point about the if you could zoom in or if folks could just zoom out a little bit beyond even this ferocious fighting in Gaza, yeah, things are very tense in the region and other, potentially other parts of the world because of what people are seeing or hearing about events in Gaza. So Hezbollah, for the past few weeks, is certainly trying to send a message to Israel that it's there on its northern border and it is engaged in these small scale attacks and Israel has responded to those small scale attacks and Israel and Hezbollah have their own cycle of conflict, that they've been locked in. But now this is this is different because it's part of the war in in Gaza and could Hezbollah escalate at some level again based on events in Gaza? If Hamas is getting to the point where they're very you know Israel is is killing or capturing significant number of Hamas fighters, and if Hezbollah perceives that or Iran perceives that, you know the relationship between those actors and Hamas is potentially going to be permanently damaged do they then get involved to save Hamas right with that. We don't know, but that is potential. And likewise, I think over the past week or so there were some report media reporting that within the first couple days of the Israeli response October 7 that the Minister of Defense or other security officials in Israel contemplated starting a more aggressive campaign against Hezbollah as well to the north, which, had that happened, I mean, this war would look much, much different. Right now that has not happened, but again, hezbollah could spark that or Israel could, could initiate that, because it sounds like they had thought about it a month ago.

Speaker 2:We've seen the media reporting too, as you noted, about these Iranian proxy attacks in Iraq, syria, yemen against US troops. Number troops have been injured is up to a couple dozen, thankfully known. It's been killed, and the US has responded to those attacks. I think was last week that there were the strikes against Iranian Revolutionary Guard positions in Syria, but the US also didn't escalate beyond that and this has been going on as well for the past three, four years separately, first with the Trump administration and Dubai. Iran and the US are just like Israel and Hezbollah are locked in their own cycle too. Now it's all part of the war and Gaza and how things go in this aspect of the conflict.

Speaker 2:Again, it could. Things could escalate very quickly, even if they don't affect the fighting in Gaza and then the reactions in all the countries you mentioned in the region and other parts of the world. I mean this is something that is affecting domestic politics. It's affecting potentially domestic security or stability in countries and just like what we saw in the Arab Spring going back a decade plus, I mean what started then now that different context, but what started then that looked like you know, these sort of peaceful protests we're going to lead to some kind of democratic change and some of these countries are political change and some of these Arab and Muslim countries turned out not to be the case and and countries got more authoritarian.

Speaker 2:Isis emerged out of the, the Syrian Civil War and the Iraq sort of sectarian political divides that were happening. So I'm not saying that is going to happen now, based on this domestic reaction to what are domestic reactions that are happening in Gaza. But again, it doesn't seem like people are happy and the more they see these images and pictures of Palestinians who aren't part of a mosque but just Palestinian civilians getting killed in the crossfire, injured. That's going to continue to to shape perceptions as well. So the region at large is very volatile. There's so many different equities and play and it wouldn't take much and I keep saying this in a lot of my interviews it wouldn't take much for us to see something that looks even worse than things look right now. But again, when that happens, if it happens, who would be involved? Nobody knows, but the conditions, I think, are there yeah, I think that's a really good point.

Speaker 1:You mentioned specifically towards the end to that, the conditions, the circumstances are set, the stages set for something to escalate broader. If, if Hezbollah engage Israeli targets and launched an invasion of any, say, capacity, it would not only turn to a two front more, but three front as well, since they have positions Hezbollah in Syria as well. So that would obviously spread the Israeli military terms of manpower rather thin. Might be a stretch but you know, would definitely stretch them quite a bit.

Speaker 2:Yeah, I mean Israel hasn't had to fight a multi front war since 1973 and they've already mobilized hundreds of thousands of troops beyond just the main force of of the IDF. So now you've got a hundred thousand troops who, at least right now, are mostly focused on Gaza. But if a second front or even a third front opens up, yeah, israel will will face an even tougher time. We also haven't talked about the unrest that's happening in the West Bank, and there's been a lot of violence that's happened there and again. The West Bank could be another one of these issues that, like the same things that are happening in Gaza, the same things could theoretically happen in the West Bank too. And even if we're only contained in that, how would Israel manage the fight in Gaza and the West Bank?

Speaker 2:and again, what? How would the world react to that?

Speaker 1:exactly like, specifically, the United States, like how much do they get involved? Well, these are, was a crew of ships that the word is alluding me, but in stations, you know, on the coast of Israel, would they engage? Has a lot of targets as well, that they got that aircraft carriers, and that's the thing too. Then how does that bring the United States into this conflict and, you know, escalate even more so to where possibly see Iran taking a larger step outside of their proxies, such as has below?

Speaker 2:yeah, these are all excellent points to, and I think President Biden and Secretary of Defense Austin have said that the reason we have put these two carrier strike groups into the region one off the coast of Israel, the other now looks like it's in the Red Sea must have gone through the Suez Canal or maybe come up another way or gone through another way, but those are positioned to provide the US with a tremendous amount of capability, with the aircraft that are on each of the carriers and the weapons that the that are on the different ships and the platforms. There are probably also a few thousand troops on those ships I think there's a couple thousand Marines were in one of those strike groups and probably other US personnel, because, based on what happens on the ground in Israel, other parts of the region and US interests are affected. Well then, those are the troops that would be the first ones to go in if we needed to evacuate an embassy or if there were, you know and hopefully this doesn't happen but a large terrorist attack against US interest or diplomatic facilities, then those troops would be there to help with the recovery and response to that. There's been some media reporting to that US special operations forces are in Israel right now more as advisors to help the Israelis figure out what to do on the hostage recovery aspect, just in Gaza, because there are still over 200 hostages and about a dozen or maybe I think it's 10 Americans that are still part of that pool of hostages. So if we have, we have troops in the region. We have tremendous capability in the region with these carrier battle groups, but I think they're there for the most part to deter Hezbollah and Iran from getting involved and if deterrence doesn't work, then to give us some response capabilities. And we a lot of your, your listeners of yours probably don't remember this, but this happened in the United States 40 years ago.

Speaker 2:In the aftermath of Israel's incursion into Southern Lebanon in 1981, 1982 to deal with then sort of the Palestinian nationalist threat from the PLO and these other Palestinian more secular and nationalist rejectionist groups. Israel went in to attack those groups that were using Southern Lebanon is sort of safe harbor and base. But things went badly on the ground there. There were these attacks by these Lebanese Christian militias that killed innocent Palestinians who are in these refugee camps. And the US got involved with other countries to help bring about a ceasefire and and provide some kind of humanitarian relief as part of a multinational peacekeeping force, and that's why we have Marines on the ground in Lebanon. But some of those ships that were also in the same kind of general vicinity, where one of the carrier strike groups is now I think it's the USS Ford, that's the carrier they were attacking Lebanese or targets in Lebanon with battleship launches. I mean, these are we haven't seen that since World War Two. And again, is that something that could happen as a result of having the capability in the region? But based on what happens between Iran and Hezbollah, does the US get drawn in? And it would get drawn in like it did in 1982. With that, or once we put the Marines on the ground, they became the targets of these large scale.

Speaker 2:Has Bala attacks the biggest loss of life and a terrorist attack. The attack started in 911 in the United States, was the attack against the Marine barracks in Lebanon by his Bala and over 240 Marines died so. And then the US Embassy got attacked in Lebanon and Kuwait by his balls, was the kidnappings of Americans and Westerners, and on and on and on. So we've also seen from a US perspective now, 40 plus years ago, what that meant for us and how it affected our interest. So and I also have to think that's, I'd like to think that's there are some people with that same kind of historical perspective. Giving advice to the White House is just caution, like if we're going to get more involved in this. We've seen what it looked like 40 years ago and was not good, and are we willing to accept the same kind of risks again? And these are all things we have to think about from the US perspective.

Speaker 1:So mainly about possible escalation, what that looks like, how will that materialize in the region and how the US will respond. What are some potential de escalation methods that you believe could exist out there Now? Right now we're seeing the biggest, I would say, pain point for these major actors in the region is the counting civilian, the civilian casualties continually piling up in Gaza is there, and we've we're actually just starting to hear from the White House to that. There is the word humanitarian pause being thrown around. Wherever that, wherever that looks like. Do you think that is like the way forward? You think that's a you know something that we should pursue more and actually take no use a carrot and stick approach with Israel for, or, and do you think Israel will even be receptive to that whatsoever?

Speaker 2:Yeah, that's a great question and it gets back to, I think, the first part of our discussion where we talked about, you know, what is the US position, or how is that position been changing? And I think this is where that position has evolved over the past month, where, whether it's humanitarian pause, ceasefire, that some some aspect of a pause in the fighting to allow for more civilians to get out, to allow more aid to come in and to get more hostages recovered, to what would Hamas be more receptive to releasing hostages if they were not under the the significant amount of pressure that they are now, both through the air strikes and the ground campaign that's unfolding as we speak? So, and that is certainly an aspect to this, but on the flip side, even if the US continues to promote that and I think the UN General Secretary has also said that that needs to happen in other aid organizations that, from a domestic Israeli point of view, president Netanyahu said from the beginning, like from October 7, that the goal for Israel is to crush and destroy Hamas, and I'm sure he's used other phrases, but that's the one that I remember and if that is the objective, then how far along are they into their military campaign where they could say we've we've done enough to get close to that objectives and we are now willing to take a pause to let these other things happen, to minimize civilian casualties and again to show that Israel is trying to abide by international humanitarian law and other standards. But he's also facing pressure politically as well and and because of the just the horrific nature of the attacks on October 7. Israel may not be in that place yet in order to allow the pause to happen, or ceasefire, whatever the right word is.

Speaker 2:So it's so complicated because you've got these external forces saying one thing and then from the Israeli side you've got a different calculus, both at the political level and, I think, within the military and the national security side of things, and and how that all plays out, nobody also knows. But I do think the more the world sees these images of the civilian casualties, of physical destruction of Gaza, the more that's just going to generate this. The things we've already talked about, this reaction in the Arab and Muslim worlds is political protests and and how that all drives towards some kind of intervention, nobody knows. But that's just. That just shows how complex things are to even try to get to the pause or the ceasefire.

Speaker 1:And it's insightful point to make mention of the political implications of what's going on right now, specifically in Israel and that domestic populace, because, you are correct, I do want the continual campaign, military campaign, to be carried out in Gaza and against Hamas, but I think it's also fair to say that there's there's a great quote on this from our class reading a too long ago. But, you know, seeking revenge, you can almost lose yourself in like the moral chaos of things was to the fact of that and you know that just speaks to like when you're going after, like following United States after 911, you know, september 12 month, two months later, I think United States was really rallied around the cause to pursue and hold these terrorist accountable, to hold al Qaeda accountable for what they carried out awful attack. But through those intense emotions, I think a lot of wrong decisions were made on the United States side. It's not that controversial opinion 20 years down the line, but when we carry that out, if there was someone saying, and someone that had influence over the United States saying, hold on a second, like we did this years before this happened to us, there's a lot of wrong decisions made, a lot of mistakes made and that resulted in tens of thousands, of hundreds of thousands actually, of people dying that maybe didn't have to. Should the United States take more of an actor role in playing that?

Speaker 1:Even though it may not be politically popular in Israel, the United States does have leverage here. We first mentioned about the A package. That would be if it passes, because Israel it's $14 billion and that's not nothing. Should that be used as a point of leverage? We need to figure some things out, such as when you spoke of if there was a pause for people to get out. It's like get out the way. Like Egypt CC leader, he specifically does not want Palestinians to immigrate into Egypt and Jordan. Same thing. So to figure out more specifics there. But I mean my first indirect question would be should the United States play more active role and use that $14 billion package as leverage to let things, let the dust settle, just so these civilian casualties can stop skyrocketing day over day?

Speaker 2:Yeah, I mean that's a great point. We don't know how those discussions are happening between the White House and Prime Minister Netanyahu, but what kind of conditions are aligned to the aid that goes forward. So that's a potential. But getting to something you mentioned a couple minutes ago, look, the US made a ton of mistakes after 9-11, and, just like Israel, we thought we had to react very quickly, not only in response to what happened, but also to prevent the next wave of al-Qaeda attacks. And I can tell you, I spent my career in government from 2002 to 2018, and those first few years after 9-11, I had a couple of different jobs, but I was sort of in the trenches of that world, so to speak, and it was daunting.

Speaker 2:I mean, despite everything that the US had done in those first couple of years after 9-11, the threat from al-Qaeda was still really high. And even though they basically suffered tremendous losses in Afghanistan after the initial campaign, the bin Laden and the leadership had to leave, and then we lost the trail on bin Laden. It went cold or it went cold. The Taliban basically gave up control of Afghanistan and kind of went underground. So it looked like we were successful or a lamp of the threat was still high, but then we did think so quickly that we put in place these policy and legal frameworks that allowed things that we thought were going to keep us safe actually wound up having these second third order effects that will probably, you know, made us I don't want to say less safe, but they just created an additional round of problems. And I teach a class on counterterrorism at the University of Michigan and it goes through this timeline approach both pre and post 9-11, to allow students to really look hard at these decisions that we made in these different periods of time and, yes, with the benefit of hindsight, to think critically about what went well, what didn't go well, and how do you assess some of the decisions. I mean, one that always seems really poignant now, 20 plus years later, is and this was the first piece of legislation that the US developed after 9-11 called the 2001 authorization to use military force, which was basically the White House's way of getting Congress to agree to allow President Bush to initiate this global campaign against al-Qaeda and using the military and other parts of our national security apparatus in a way we never did before 9-11. But that bill was passed in a week, a week after 9-11, and it was completely open-ended in the sense of giving any president that authority to go after the groups or people responsible for 9-11, without any sense of geographic boundaries, any notion of duration. And here we are, 20 plus years later, and that 2001 authorization to use military force is still in the books. The Biden administration is using it as well for counterterrorism.

Speaker 2:And the lone member of Congress, or at least in the House, that voted against it was one person. So in the House of Representatives, I think the vote, the floor vote, was September 14, 2001,. A single member of Congress voted no and she Barbara Lee, from California, and she was attacked politically for being un-American and saying how dare you not support the overwhelming majority of where Congress or the House of Representatives wants to go? And 20 years later, that single vote of saying and she didn't say we didn't. She wasn't saying we don't need to respond, she was just saying we need to think this through and be a little bit more deliberate before we run off to the races and probably start making a bunch of mistakes.

Speaker 2:And maybe this is a long-winded way of saying that Barbara Lee's principled position on September 14, 2001, actually turned out to be a pretty prescient insight and whether those conversations are happening with the White House even after President Biden left and he basically kind of said some of those things in his one televised speech while he was in Israel. Whether those same kind of conversations are happening between folks in the White House or folks in US Congress and their counterparts in Israel. We don't know. But we have our own track record of things to consider after 9-11, and some things went well but some things didn't and hopefully Israel is taking that same, is taking that advice, if they're getting it to account as they're conducting the campaign that continues and, again, it's probably going to continue for quite some period of time.

Speaker 1:I appreciate the insight there and that's a really good call out with Barbara Lee. I know it's that close following the attack on September 11th but say, as I mentioned with it's more than just a vice that the United States can offer or has. As I mentioned, karen and Sticks.

Speaker 2:Right, yeah. And then politically, like again, is the White House willing to use that as a stick? But if they are and again, like these are all probably very private conversations then if that gets out, where the Israelis will say, well, yes, the US was willing to give us $14 billion in aid and maybe that's just the first package, but they're also saying we're only going to give it to you if X, Y and Z happens, or there are these kind of conditions wrapped around it, Then again there's a political reaction to that here domestically.

Speaker 2:So, it's just it's hard to know if that is going to be used as a stick, as opposed to just getting the package out now to hopefully allow Israel to achieve its objectives quicker. And if they can do it quicker, hopefully that would thereby minimize and prevent further civilian casualties. But regardless of how long this takes, there's going to have to be a day after scenario too, and no one is really talking about that in the sense of well, whatever Israel thinks, that will achieve its military objectives against Samoas and again, it's hard for us to know that here. What happens to the Gaza Strip? What happens to the hundreds of thousands of people who either have stayed or the ones that have left but want, you know, temporarily, but want to come back?

Speaker 2:Who is going to administer the Gaza Strip and who is going to rebuild it? I mean even from what we see now. I mean significant physical destruction. This looks like it's the same bombed out landscape that looks like what we've seen in other places of the past 20 years Parts of Iraq and Syria. Iraq first, through the first, you know, the war from 2003 to 2011,. And then the fights against ISIS from the mid 2010s to the end of the decade. I mean the same physical condition happened in places like East Mosul and Raqqa, syria and other parts of the region, and there's going to have to be significant reconstruction and relief efforts that will have to occur to rebuild the Gaza Strip.

Speaker 1:For sure, and I think that's a great segue into the article that you sent over and read and reviewed, and I thought it aptly point out the difficulties of urban warfare and drew parallels between what Gaza may look like and may look like and what Iraq and Syria look like. But I am also curious, similar to how you know, the war in Iraq became viewed as unpopular by the American public, unpopular, that is. Do you believe Israel, the Israeli public is will? Will that support Wayne over time as well?

Speaker 2:Yeah, that's a great question. Right now it doesn't appear to be. I don't know if there's polling numbers or any other concrete way to measure that, so all I can, you know, all I know is what I read in the in the papers. But the political support or political support for the war, or popular support that's a better way to put it seems pretty hot because of the nature of the attacks on October 7th. But if the fighting continues for a really long period of time and if the IDF continues to take a pretty high number of casualties, unlike other campaigns they fought against either Hezbollah or Hamas over the past couple of decades, does that turn the tide of public opinion in Israel? We also don't know the answer to that, but I do think it's striking and I always hate talking about these numbers because we're talking about human beings and human lives but the last major Israeli ground operation into the Gaza Strip was in late 2008 into early 2009,.

Speaker 2:About three weeks long, and Israel declared a ceasefire after after that and and they suffered about over a dozen IDF fatalities and probably higher number of casualties.

Speaker 2:Hamas claims they suffered 6700 dead fighters and a couple thousand Palestinian civilians, and always the Palestinian, I mean the civilian numbers are always higher than the combatant sides, and that's just the nature of these, these urban fights. But I guess on Tuesday again, I haven't caught up with every single day's worth of reporting, but on Tuesday alone the IDF claimed they lost 15 soldiers in one day, which is more than they lost in the last major ground campaign against Hamas, going back 15 years, and just like what we're seeing in Russia, ukraine, with these terrible casualty figures on both sides of 100, probably tens of thousands, of hundreds of thousands of combatants killed or wounded on both sides. How, how bad will this get for the IDF before the public pressure becomes so significant where, even if the military objectives aren't met, prime Minister Netanyahu and the senior folks on the IDF are going to have to rethink sustaining the campaign? And no one knows what that will look like either. But I think that will be another factor that will drive the outcome.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I mean from to my knowledge, and this is reported by breaking points of independent news outlet, but they were saying that the battle in Mosul that you talked about in your article, that the civilian casualties matched up with the armed and surgeon casualties, isis was a one to one ratio actually, and then so for every fighter that was killed, the civilian that was killed. And then in the war in Ukraine, I believe it's also been signed that around 10,000 Ukraine civilians have been specifically killed thus far. So the ratios seem to be a bit different. I think, obviously, gaza is much more densely populated and packed in than Ukraine, but I think this is like the go to point that we're hearing, especially from certain commentators, is that this is just war. You know so and that that's true to extent. But I believe, as the Geneva Convention conveys, states that you need to do every kind of minimize those civilian casualties, and that's where I believe a lot of people pushing on that.

Speaker 1:I don't believe you are doing everything you can to minimize those civilian casualties and it's it's closed with this last thing, that we saw a strike in a refugee camp in Gaza and the international spokesperson for the IDF was, you know, in a pretty tense interview with Wolf Blitzer and he's like you knew women and children were there, right. And he's like, yeah, and we also knew that there was a, a hospital in commander was there? What's like, what's your point? This is war. I think that is just really going to not. It's not popular. I don't think it's going to stay popular for much like with anyone, if whatever was.

Speaker 2:But I think that kind of the fault line is quickly running out of fuel because it's just obviously there's a disparity, and maybe that's why this, this battle, looks different than even the other ones that I mentioned in the article.

Speaker 2:You mentioned, too is that because Hamas has sort of buried a significant percentage of its military and terrorist infrastructure deliberately in these civilian locations, they're almost daring Israel to hit them. And Hamas officials have, too, said some really terrible things, were even acknowledging the fact that Palestinians, civilians, are getting killed or injured in the Gaza Strip. They also have kind of said well, this is just the cost of, this is just the cost of of our struggle, and they're all now going to be received as martyrs. So there's an equally ruthless perception on this from the Hamas side too. And in least in Mosul and the fights in Fallujah going back to 2014, 2005,. Before the camps had pain started, there was a significant attempt to get a lot of civilians out, as many as they could. Now didn't mean that everybody left, but significant portions of both those populations in East Mosul was like 10 times bigger than Fallujah, but a lot of the civilians did get out.

Speaker 2:Maybe that's why the casualty numbers were lower but, because so many Gazans have not been able to get out and it's such a densely packed environment, and Hamas is deliberately putting parts of its military and terrorist infrastructure in these civilian sites that Israel will claim just probably like the interview that you referenced From the Israeli point of view, it was a legitimate military target, and this is just another tragic reality of the conflict there. Maybe that's why it's different than even the other ones that I tried to describe.

Speaker 1:And I think that all plays true. That's interesting. I'm glad you pointed out the fact that there was a time in previous conflicts where there's an opportunity for civilians to leave, but what you just mentioned at the end, that this is just a fortunate reality of war, I think that excuse is really just going like To fail with the broader, as it already has with the regional actors there. They're not gonna take that, but not accept that. Iran's not gonna accept that has bloods, not accept that. If they were to accept anything, turkey, erdogan like no, he's like more like populist try figure. But that's that's the concern I see because of these civilian casualties continue. But playing aside the humanitarian crisis, if the civilian casual and just from a political analysis at analysts perspective, if they continue to amount to these extraordinary levels and that's just to go to line, then the more outrageous going to continue to grow in that region and almost bode other actors to enter this conflict because there's such a disparity in what is going on and in the refugee camps. Like it's. It's awful because it's just it's terrible and it's not good and that's the concern because no other actors and this war is Like Israel at very real risk. And then that also brings the United States into the war to extent, or most likely would, and Minimum.

Speaker 1:But I do want to pivot to something else too, because I know you have extensive experience and number of areas and I recently saw an analysis On something. I want to get your thoughts on it and see if you even believe it's true. But the Israeli government used to leverage its intelligence agencies, such as and Massad, to launch these special operations and target specific personnel in the ranks of extremist terrorist organizations. You know, the best example this I could think of is black September, following the 1972 Munich Olympic Massacres. However, since mainly Prime Minister Nanahu has inner powered in the late 90s, 1996 I believe, the Israeli government has really leveraged its entire military to carry out these broad striping strikes. Do you believe like, how do you view this pivot, if you believe it at all, and do you think this it's like the right move or do you think this has kind of created maybe more of a radical, traumatized population of people?

Speaker 2:Yeah, that's a good question. Um, well, in the past, the, when Israel was using that tactic, the groups that they were fighting were, for the most part, relatively small and clandestine. But over the decades at least, you know the print. Their principal adversaries now it's not the PLO, it's not the Palestinian Liberation Front or the Palsed. You know the PLF and all these Nationalists and secular groups that Israel was fighting Up until the the late 70s into the Early 80s. Now, with Hamas and Hezbollah, they they have tens of thousands of fighters each, and Hezbollah may have even more.

Speaker 2:And Hezbollah actually looks more like a military than a Terrorist group, and maybe that's why the IDF has had to Scale up its response.

Speaker 2:Well, we can't just use these surgical strikes against key figures, either in the region or or elsewhere, because we're facing a very different kind of threat that isn't just trying to put a single suicide bomber or launch a single suicide bomber against. They can drop, like Hamas did, three or four thousand rockets in a couple hours and, you know, push in Thousands of fighters across our border. That is a very different threat than classic terrorist type operations and an activity. And but one would have to think that Israel still has that capability and Will. At what point would they try to use it against Hamas officials or leaders who are outside the Gaza Strip? We don't know the answer to that question, but that would just be a part of a military campaign that looks like Something that Israel did in 67 and 73 against armies, because they're using air strikes, they're using ground operations, they're integrated now in the Gaza Strip. That's a very different response than the one they used decades ago that were much more surgical and much more Limited and.

Speaker 2:I think that's a reflection of just the threats that look different to them.

Speaker 1:Understood. Speaking directly to the terrorist attack on October 7th, you recently stated an article that to Execute a strike like this, like how Hamas really coordinated all this and carried out a similar day, they have To at least gone to great lengths to conceal the plying from Israeli intelligence. However, it's also been widely reported that Hamas was open about the preparations for attack or maybe public Would be a better word. For example, according to Reuters, a source close to Hamas said that they create a mocks Israeli settlement in Gaza, where they practiced a military landing and trained to storm it and unquote there, but they even created videos of the tactics the article went on to mention. Following that, an Egyptian intelligence official stated that Israel ignored warnings of quote something big. So this really involved these extremely covert preparations and operations.

Speaker 1:Or Was it simply a neglect of the intelligence agencies to have some kind of cohesive communication, a Structure or person position in place? Like you point out, following 9 11, the one the recommendations from the 9 11 commission was to put together a person I believe is now it's the national intelligence committee that is connected with all these different Intelligence agencies to make sure there's no fragmentation in terms of the information that we're receiving and people left hand is talking to the right hand. So what were you? Have you thought more about there? Have your thoughts changed since that about, um, how this could have been prevented, or how, or what Israeli intelligence may have known?

Speaker 2:and, yeah, I think the question, I mean the, the story is still Unclear, even though there are sort of fragments coming out about what Israel may have known in the run up to the attack. And it was clear, I mean, there was there. This was an intelligence failure. There's no other way to describe and the Israelis themselves have admitted that that they, they failed to prevent this Detected or prevent it from from happening. But the, the actual sequence of events of who knew what, when and how much do they know? And how was that information being Sort of treated and assessed? And and how was it flowing all the way up to the prime minister's office or Heads of these different services like? We don't know the answer to that and it took the united states Almost three years to get a public accounting of that through the 9 11 Commission and, I think, israel whenever, whenever this military campaign is done again, nobody knows when that's going to happen, but they're going to have to answer those questions and they're going to have to have some kind of Accounting of what didn't work to make sure they don't have another failure like this Again, because the implications are just so severe and it took us Three years to get that story out through the 9 11 Commission, and one of the key recommendations of the 9 11 commission was the creation of the director of National intelligence in the office of the director of national intelligence and some of these bureaucratic structures that came into place and I served in my time in government, and some of them by the late, early 2010 so I saw firsthand sort of the value of having these new positions or organizations in our intelligence community focused on counterterrorism.

Speaker 2:I think that's a good roadmap for what Israel needs to do, because, just like us, they have these world-class intelligence services, but we're probably very Stoke-piped and there are also cultural issues that come into that. When you think like you're really good at something and you don't, you can do your mission without anybody else's Help and you don't necessarily need to share or pass information and you want to treat it more as like your services and not like the government's writ large, that can lead to these problems, and these are exactly what happened to the United States free 9 11. So I would think that eventually, israel is going to have to enact some serious reforms with this within its intelligence structure, um, to make sure that people are collaborating, they're integrating and they're sharing information as a matter of practice, not just, you know, on an ad hoc basis, and these are all things that it took people in our government years to embrace. And there are still probably some people who think that the things that we did after 9 11 aren't a good idea, and I acknowledge that it's not 100% Uh, cohesion on that.

Speaker 2:But they're always going to be naysayers whenever you make Significant policy and strategy changes on national security. Um, you just sort of accept that. So I do think Israel is facing that moment, but I don't think right now they just have the time to put those measures in place because they haven't even achieved, I think, their military objectives in this campaign. But probably a couple years from now will, we'll see what these intelligence reforms Look like in in Israel and how much of the Hamas planning was out there in the open and how much of it was completely covert and clandestine and beyond the the reach of israel's Intelligence capability. It just it's hard to know, but the bottom line is they missed it.

Speaker 1:Well, I thank you for all the insights shared. I really do. I really appreciate it. I think my listeners will, too. Just really listening to this as well, like this really is meant to give a perspective on how the United States should prosecute or maybe interact, moving forward or approach this issue overall and approach this conflict. But I do want to ask you two final quick questions, which is, if someone is trying to understand, maybe, the geopolitical implications here or just what is going on and how to track it, where would you point them to? And, secondary, if someone to keep up with you specifically and your media interviews and your commentary and articles you publish, where could they find that at?

Speaker 2:Yeah, good, well, I'm probably more helpful on the first question than the second one. But on the first question, I get my information from three primary sources. On my phone I don't unless I'm on TV is going to sound dumb, but I actually don't watch TV unless I'm giving an interview, because again like you can just kind of get drowned out in the noise of cable news and other television.

Speaker 2:So, even though I'm on it a lot, but on my phone I have three media apps the Washington Post, new York Times and BBC and that's a good cross section of different platforms with different reporters and insights, and those are the things that give me the best insight as to what's happening on a day-to-day basis and I spend probably half an hour to an hour of my time just reading the content that is on those platforms and that keeps me I feel like that keeps me pretty informed in a way that's just better than watching television or social media. And I also know a lot of the reporters and producers. So I have confidence that these are people just trying to get the facts out and the news out, versus something that has more of a slant to it. And so I'm always and that's the maybe getting into the second question that's sort of the role that I try to play in the media. I'm not there to push a personal narrative, I'm not trying to endorse a political view. I'm just there to be an objective analyst, kind of like what I tried to do in my time in government.

Speaker 2:Doesn't mean I'm going to be right and doesn't mean that people are going to agree with what I have to say, but I don't try to pick sides. I just try to give a perspective based on my perception of how things are going. That's based on experience as well, because I wasn't an academic until I started teaching in 2018. So I don't look at this from an academic perspective, but I unfortunately don't have a social media presence. So I don't post the stuff that I do on a social media platform. But just because I cover this range of different platforms, that certainly in moments like this, you might see my name in a paper, you might see my face on television, but I don't beyond whatever you know fleeting kind of presence there is. That way, I don't bundle everything up and then you couldn't go to one source to find all that.

Speaker 1:Understood. Well, I still thank you for your time. I think there's a lot to take away from this conversation. I look forward to listening back to it in that process. But yeah, thank you again for being here.

Speaker 2:Absolutely. Thank you, Daniel All right society.

Speaker 1:blinds are going to talk to it in the future Global Studios.